11.17.2015

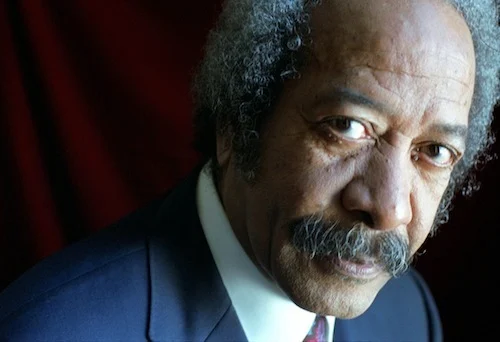

ALLEN TOUSSAINT (1938-2015)

The Audacity Of Despair: David Simon: 10th November 2015.

I woke this empty morning to the sudden departure of a great and good man.

There will be many better, more comprehensive tributes today from musicians, music lovers and New Orleanians who knew him well, so don’t stop here without going further to celebrate Allen Toussaint’s life. I met him on only a handful occasions and then only in a professional setting; others can attest to so much more.

But there are a couple of warm anecdotes that I treasure and that ought to be added to the day’s reflections on a gentle, giving soul and one of the finest composers who ever created American music.

I had a few rare opportunities to share time and space with Mr. Toussaint during our four seasons of filming “Treme” in New Orleans, on those occasions when he allowed us to portray his person and his music as part of our fictional, post-Katrina narrative.

Among other things, “Treme” was our attempt to depict the New Orleans music community as organically as we might in a make-believe television version, and to give voice to some of the extraordinary talent and craft of that city’s song. There could be no attempt at such without Mr. Toussaint engaged.

He understood our intentions and purpose immediately and made himself available not only to honor his own artistic contributions — which are vast and enduring — but those of other artists, for whom he arranged live, on-camera performances and then accompanied with his requisite precision at the piano. He gave himself over to these moments easily and warmly. Irma Thomas, Dave Bartholemew, Lloyd Price, Art Neville were all out front on the show with Mr. Toussaint’s backing, and it occurred to me only later that he had given so much care to the performance of others that we had, in the film, more of the man’s music performed by others than by the man himself. I regret that and fault our planning, though Mr. Toussaint, typically, never mentioned it.

Independent of the film, Mr. Toussaint performed a version of “The Greatest Love” as a duet at the now-gone Piety Studios in the Bywater, with Elvis Costello on vocals. It strikes me now, this morning, as one of the most singular moments of musical performance that I have ever witnessed. We recorded it for an HBO video release at the time; if I can locate a download, I will post it later today and your breath, too, can be taken from you for some moments.

But for the man’s charm, I can offer three small anecdotes from that same day in the Piety studios.

In the first, I sat behind Mr. Toussaint in the control booth while he rehearsed his hand-picked New Orleans horn section on the lines of “Tears, Tears and More Tears.” This collective, an all-star revue of the city’s best brass players, also included one Wendell Pierce, who was, as a “Treme” actor, pretending to be a part of that august group. Mr. Pierce, who had been trying to learn some of the trombone he was pretending to play, had it in mind to contribute in some small, personal way to the musical moment.

Quietly, he slipped off the bone’s blocked mouthpiece and put in the real one, and then, as Mr. Toussaint talked about unrelated matters with Mr. Costello, scarcely paying attention to the rehearsal, Mr. Pierce attempted to add a few notes to the arrangement.

Mr. Toussaint wheeled.

“What was that?” he inquired, hitting the control room button.

The horn men stopped. All of them knew, but none of them felt an immediate need to give up the imposter, so Mr. Toussaint asked each to play his line individually, nodding softly at the notes. And then, finally:

“Wendell? Did you play something?”

“I, um, I might have let a few notes go.”

“Wendell,” said Mr. Toussaint quietly, with the trace of a smile. “Please don’t.”

And later that evening, there came an even more wonderful moment when our film director, Jim McKay, attempted to call action to a scene not merely by rolling speed on sound and calling camera and action, but by actually — I kid you not — attempting to count down Mr. Toussaint’s band, as if he were Lawrence Welk coming out of a commercial break: “And-ah-one, and-ah-two, and-ah…”

The musicians stared at him blankly, fixed and immobile.

Quietly, at the piano, Mr. Toussaint gave a small cough to break the stillness.

“Sorry about that,” Mr. Toussaint said. “Some sheep only follow one shepherd.”

After which, he kicked them off.

I have another memory of that special day, which involves Mr. Toussaint noodling at the piano in a lighting delay — a tune very much unfamiliar to me, but not to my wife, who though no student of New Orleans rhythm & blues is nonetheless a maven when it comes to Broadway musicals.

“Excuse me, Mr. Toussaint,” she said gently, as if she barely had standing to inquire. “But is that the overture to Brigadoon?”

He lit up.

“Why yes, young lady, it most certainly is.”

And he played it for her proudly. Later, there was a moment when we were listening to playback of a scene and Mr. Toussaint sat next to Laura on a bench, taking in the music, nodding his head thoughtfully. And then, as the song concluded, he reached a long, graceful arm above his head and played a single note on a toy piano that was on a shelf above him. He did so without looking, with one finger expertly poised.

It was the right note. In the right instant. Tink.

Then he lowered his arm and looked at my wife slyly and she fell promptly in love.

No worries, Laura. I did, too.

Allen Toussaint & Elvis Costello “The Greatest Love”