12.16.2015

POST-PUNK POLYMATH

Dublin Review of Books: John Fleming: 1st December 2015.

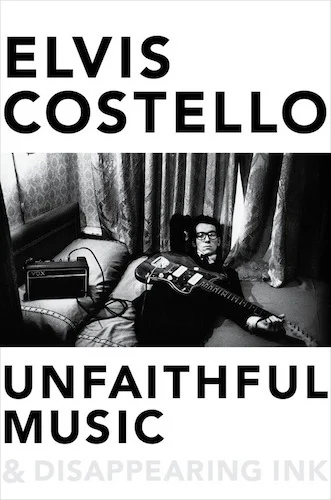

Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink, by Elvis Costello, Viking

Frantic broken puppets half-twist and force music from instruments they seem to disdain. Steve Nieve waves fingers in dismissive flourishes over the unstable keyboard, as if trying to magic away its swirling sound. Peter Thomas is banging the drums, with the precision of a riveter. Bruce Thomas rotovates a deep tonal landscape with his cinematic and seismic bass. And an articulate young man called Elvis Costello thrashes in apparent scepticism at a guitar in which his surname has been embedded in silver lettering along the fretboard. Malarial sweat rolls from his face as he glares bug-eyed through glasses, mouth moulding a new wave sneer as the stage lights shift through the primary colours: violent red, migraine blue and jealous green. It is June 1978 and Elvis Costello and the Attractions are belting out Lipstick Vogue in the WDR studio in Cologne for a Rockpalast television broadcast.

Almost four decades later, Costello occupies a strange cultural perch as a literate dramatist operating as always through the medium of songwriting. A collaborator of extreme promiscuity, he has evolved into a grand old man of music who has crept across borders into nearly all the protected and cordoned off musical genres (classical, country, opera, jazz,R&B). Dragged behind what many must see as enemy lines, his fan base has reaped mixed rewards, deciding to stay loyal to the man or defect as tastes dictated.

Costello’s vast autobiography comes as a treat for this diehard fan of his first five or six albums. It is no surprise that one of the best lyricists of the punk rock wars should be able to deliver an engaging and articulate work. And for a man who used to punch out an album with a free EP, plus a brace of singles with extra B-sides each year, it is no shock the book should be so long.

A post-punk polymath, Costello shifted gear in the closing years of the 1970s from the tersely monochrome anger of the Clover-backed My Aim is True (1977) album to the spectrum-refracting richness of This Year’s Model (1978) and Armed Forces (1979). Then he navigated sideways towards Stax and Motown in Get Happy (1980) and to Nashville with Almost Blue (1981), along with the emergent lushness of Trust (1981) and Imperial Bedroom (1982) as the eighties got under way. But words such as Stax and Motown were historical terms to a listener limited by the infinity of punk-fuelled new wave and the literate possibility of its dismissive youth. They were “musical” terms mentioned reverentially, often by mod revivalists, in interviews in the New Musical Express and the rather soggy Melody Maker. They sounded like lessons to be learned and cast Costello as an intimidating pedagogue to the perhaps reluctant learner.

But Costello still served it all up with a characteristic swagger and intensity: there was a committed belief in music in there with his pop razzmatazz of polka-dot shirts and sharp suits and the sturdy clan articulacy of his four-man band. There was something honest and reverential in his musical reinvention. Ongoing experimentation would drive his progressing (if not progressive) rock in the decades that followed. On a creased VHS recording of the 1981 South Bank Show about his big trip to Nashville to work with the late Billy Sherrill (a big country and western producer, the documentary told his fans), it became apparent that Costello was a craftsman, a melodic lyricist for hire in the service of his own musical obsession. To him, the musical past was extremely relevant, a wishing well to be usefully dipped into. As he observes here in the book of his life “ … performance doesn’t require the qualification of being either ‘country music’ or ‘soul music’. It’s just a human with the unique gift of an instrument, telling you everything you need to know about the bleak comedy of love in two and a half minutes.” And, more generally again, conjuring up the earthy spirituality that only the foolish would choose to deny permeates pop music, he writes: “These songs are there to help you when you need them most. You can stumble into them anytime, like the noise and benediction of any basement dive.”

Costello comes across in these pages as a very decent man, one whose cynicism about the music business chimes with his early anti-rock-star antics and demeanour. There is a maturity in his self-criticism and something honourable about the complete lack of backstabbing of people who must have crossed him over the years. His world view is hugely moral and self-reproaching, but his brushwork appears at times rather broad. Whether motivated by efforts to protect himself from gory details or out of a more noble kindness to spare the feelings of others involved, he tends to allude to rather than describe incidents that clearly cause him to hang his head in shame. He imparts ruefully the insight he may have acquired into his own frailty rather than presenting the facts of the associated misbehaviour. Backdrops to early songs that crackle with the electricity of possessiveness, emotional betrayal and hurt are suggested here but mainly with mere reference to those very themes of possession, betrayal and hurt. He takes such themes of songs and tells us these themes are anchored in his life, but usually without specifying exactly how. Infidelity stalks the pages, but this is no confessional. From his early days as an emergent pop star on the road, he harvests his understanding with tools of intelligence rather than visceral or lurid replays. Is he just being a gentleman or is he running scared? Let the reader decide. He would not be alone among artists in letting words rather than feelings be the units of his medium. He sounds a few chords suggestive of this approach: “I’d become expert in writing in the dark, as even pausing to reach for the light switch could scare away the thought … The proposed titles read like a script … It took me nearly another ten years to finish writing about the misery I provoked and the darkness that could envelope two people once so brightly in love.”

There are far more direct emotions and anecdotes in accounts of his beloved father, Ross McManus, a singer with the Joe Loss Orchestra and later a type of musical jack of all trades. It is tempting to suggest that Costello’s clear love for his father was an attempt to bond with a man all too often away on musical tours and with a weakness for falling into the arms of women other than his wife. The father comes across as an unlikely charmer and ladies’ man embroiled in a phase of popular music closely allied to the hovering ghost of vaudeville, in which the aesthetics of a simpler showbiz world revolve around entertainment. Ross’s profession necessitated him bringing home all the latest records for impartial listening with a view to mastering suitable tunes for later reproduction to his big band/show band audience. This imitative activity sheds some procedural light on episodes in Elvis’s life. Young Costello buys every country record he can get his hands on and whittles them down to a shortlist of thirty-odd tunes to bring to Nashville. In an earlier exercise, he stockpiles Stax and Motown records so that he and the Attractions can steep themselves in such music to create the generous twenty-tune homage of Get Happy with Nick Lowe. Formative years include a teenage Elvis in Liverpool emerging after a childhood in London from which he relocated with his mother after his parents split up. His father’s parcels of records, US imports and promo acetates feed the boy and introduce him to the wonderful wideness of music. Costello listened and learned, studying variety and style with his ears, plucking out and keeping the records he liked most, first hearing and falling for the Beatles in this way. A whirlwind of music enters his mind and heart as something that can be appropriated, imitated, pastiched or, better still, drawn upon.

Rock’s rich tapestry (note to the unfamiliar: this was a succinct, lore-filled phrase used in the New Musical Express, a publication itself fabled in its late 1970s and early 1980s incarnation) is an influential and hardwearing floor-covering. Costello is both a participant observer and zealous sentinel among rock’s practitioners. To read his lifelong enthusiasm and reverence for music is to remember that tapestry is a magic carpet woven for us all from our early musical moments of fan discovery, be it of musicians of mass appeal and great success or minor obscurities mainly unknown. As we go through life, we might never develop a passion for morsels of music. Or we might relinquish it. But far better, we might cling to it, rejecting any accusation that our affection might be an immaturity out of which we should have grown. Songs are things we love: melodies twist into us, they poison and preserve us, a lyrical line becomes part of your life line, a drum intro or bleating note can infect you with an illness of which you will never be cured. You can remain blissfully scarred by the scratches on records you acquired and will always keep. Despite a suspicious taste for the obscure, I have no idea who David Ackles was but many thoughts about music are triggered for me in wanting to quote Costello here when he writes: “I have no explanation as to why the David Ackles albums spoke to me so intensely, but it was with these records that I probably spent the most time when I was about sixteen, listening in a darkened room, trying to imagine how everything had come to exist.”

Returning to London as a computer programmer, Costello records clandestinely afterhours in his kitchen, banging out songs that would be the backbone of his debut album My Aim is True. His affection for producer/musician Nick Lowe and his work with the maverick Stiff record label is presented in a matter-of-fact unmythologised way: he is booked to record at Pathway Studios in Islington, which “looked like a place where you might get your bicycle fixed”.

Apart from words on his grandparents, parents and half-brothers, and his wife and three sons, Costello’s most tender moments come in his descriptions of the personalities of musicians he loves and respects: Bob Dylan, Burt Bacharach, Allen Toussaint, Paul McCartney, Chet Baker, Robert Wyatt, the members of the Brodsky Quartet, the Attractions themselves. There is a brief mention of “sherbet fountains and penny chews” but Costello avoids any easy nostalgia for the postwar 1950s into which he was born. Occasional details leap from his prose like evocative lyrics: reminiscing about his grandfather, he writes “my Papa, not being a practical man, had Sellotaped the runner of the carpet when a stair-rod came unfixed”. There is a warm nostalgia in his recollection of his Nana’s use of the word “several” to suggest seven of something. In another striking aside, he refers to his son at six fretting why “nobody seems to like him” as he listens to The Beatles’ Fool on the Hill – he may be joking when he suggests the easiest solution now is to phone up Paul McCartney who wrote the words for advice on how to reassure the boy.

The dignity of labour and a sense of hard work are conveyed throughout the book. Costello is clearly no slouch: he is driven by curiosity and the notion that being blessed with a talent means you have a duty to use it. His father’s livelihood as a jobbing musician seems to have instilled in him a need to put in the hours, but also a keen sense of the cruelty of fickle show business, as in this account: “I listen to the radio late into the night, waiting for my Dad to arrive from any workingmen’s club engagement within driving distance of Birkenhead. My Nana prepares sandwiches and a bottle of Guinness on a side table, I might get to share the beer with him at this hour. It is 1971 … I tell my Dad about the earnest song I was trying to sing earlier that evening in a folk club, but our worlds are very different … He recounts the fates of failed acts or ‘turns’, faced with the indignity of being ‘paid off’ – that is sent on their way without completing their engagement rather than left at the mercy of a disapproving or hostile crowd. It’s no easy life. He tells of the desperate characters clinging to the edges of fame: eager girl singers, eccentric ventriloquists, and sullen comics, some of whom conform to the sad-clown cliché, others who turn into belligerent drunks.”

He describes an early occasion in which he joins his father onstage: “I’m huddled with a sceptical band behind a lowered curtain, struggling to get my guitar in tune … The compere finishes reading out a list of bingo numbers and coming attractions and begins our introduction … My Dad gives me a final look of encouragement and checks that I have the right opening number. I know he is happy to have me there with him, but his urgency also says, This isn’t a game, this is my work.”

Such moments are evocative and enlightening. While they excavate a troubadour gene, they also shed light on father and son lineages everywhere. On this he writes succinctly and with salience. But accounts of his grandfather playing as a musician on a liner back and forth across the Atlantic and of his First World War experiences simply fail to engage. The book sags occasionally for this reason: it could have done without some chapters and could usefully have been shorn of say two hundred of its pages. But perhaps Costello is simply worth it – the Midas touch he has always had with music saves the day and, after a run of wayward paragraphs, he always gets back on track and hits you with something memorable and insightful. Take this on Declan MacManus’s stunning show biz stage name: “The decision for me to adopt the Elvis name had always seemed like a mad dare. A stunt conceived by my managers to grab people’s attention long enough for the songs to penetrate, as my good looks and animal magnetism were certainly not going to do the job.” Describing how he comes unstuck as a former pop star with a fall from Top of the Pops fame, he writes lucidly: “Otherwise I’d think of those years in the mid-’80s as ‘The Land That Music Forgot’. A lot of the hit records of the time were not songs as I understood them, but shiny, open-ended sequences of music, mostly conjured up in the studio. I tried to go along with the plan for a while but I felt like a blacksmith in a glass factory.”

“Blacksmith” and “glass factory” are workplace references which resonate within the oeuvre of a man who wrote songs called Hoover Factory and Shipbuilding. One might be tempted to widen this into detection of an ongoing theme to do with establishments, as per Chemistry Class’s lyric “They chopped you up in butcher’s school / Threw you out of the academy of garbage / You’ll be a joker all your life / A student at the comedy college.” And as for the 1996 Grammy Awards, he writes here in familiar terms: “I felt like a spy who had infiltrated Show Business School.”

Chapter 23 is called “Is He Really Going Out With Her?”, a good-natured reference to Joe Jackson’s song of almost the same name. Elsewhere in the book, Costello refers to Jackson as a talent. Back in the distant past, the music press perceived a vocal similarity between the two. Some similarity might have also extended to Graham Parker, an original who predated them both, and indeed The Jags, a less original, short-lived act, who followed them. Jackson’s debut album Look Sharp (1979) shared some of the world view of My Aim is True. When Jackson’s On Your Radio came out that same year, some rather facilely detected a conceptual similarity to Costello’s Radio Radio. Joe at the time masterfully pointed out he had written and performed the song long before Radio Radio appeared. While none of this is alluded to in these pages, it is encouraging to see Costello joke with a chapter title.

I have only seen Elvis Costello in concert three times – and always at the Stadium in Dublin – in around 1980, 1983 and “more recently” in 2002. The first time he played I shook his hand outside on the South Circular Road through the window of a limousine, passing in a piece of paper which he and all the band autographed for me. But when it came back out through the window someone else made off with it, to my eternal dismay. The second time, the band were in a white van and I got the picture sleeve of the Clubland single signed by all the band but sadly not Costello. The third time, as a thirty-seven-year old, I did not hang around outside the Stadium for my teenage zeal had understandably waned. I also met him in 1985 at a Pogues sound-check in McGonagles. Some fellow communication studies student friends and I had blagged our way into doing some videoing. Costello was there that afternoon but would not co-operate or give an interview. Or even be civil. He was snide and I came away disheartened at a hero. Two years later in London, in 1987, I passed him in Ladbroke Grove. He wore a herring-bone overcoat and had an album under his arm. He smiled and said hello. However, I had ceased listening to his new records some years beforehand, as the energy of the new wave dissipated and fussy brass sections entered his music.

He went on to grow as a sophisticated musician, a songwriter of subtlety and a collaborator of great note. On the relationship between melody and lyrics, he has this to say: “One lesson I learned from writing with Paul [McCartney] was that once the melodic shape was established, he would not negotiate about stretching the line rhythmically to accommodate a rhyme … Burt [Bacharach] is even more unyielding once the melody is written … Not being a lyricist, he had never given himself any reason to cheat. I cheat shamelessly. The unevenly apportioned lines of my early songs drove The Attractions mad. They were difficult to memorise, as no two verses were exactly alike.”

Speckled throughout the book are a few short sequences introduced as short stories. They have something of the flavour of Pinter’s more or less adjective-shorn prose, and seem to be offered as sublimated insights into Costello’s fears and worst experiences: “It was raining hard on one side of the building as Inch took shelter inside … Whenever he was fool enough to come here, Inch always felt as if he had entered in the middle of a private conversation that he would never understand … The cackling laughter of the two men followed Inch outside until the sprung door slammed shut behind him.”

This book is a smart, considered account of the life of an artist. It turns a spotlight on pop music and entertainment, as well as on the process of collaborative songwriting, as Costello eventually gets to work with many of his idols: “I know I never expected to meet half the people who I’ve encountered down these years and across these pages. I thought they were just names on record jackets, reputations spelled out in the lightbulbs of a marquee, or consoling voices in the dark, but that’s not the way it has turned out.” Towards the end, he pulls together various strands explored when he writes: “I see no way to stop now, whatever stage I’m standing on or if my songs should be distant memories or widely distributed in pill form like the food of astronauts. This is not an occupation. I believe it is a vocation. One can mean you’re just taking up space and burning time, the other cannot be denied.”

While his career has waxed and waned, Costello’s endurance and effective permanent success suggests he will persevere until he drops. He will keep writing songs and mastering styles, living in music whatever about the public eye, always incorporating what he learns from other musicians and what has been handed down to him from father to son. And whatever about the eternity of cultural artefacts such as records, pop videos, magazine covers and now this book, the sixty-one-year-old remains conscious of one thing: “When your name was printed just above that of the liquor licensee at the bottom of the bill. That’s where we all start out and that is where I suspect I shall return, and none of this that I am telling you about will matter then.”